|

Richard B. Sigle

Sign Our Guest Book

From the Prairies to the Skies | home

The Family | Growing Up | Life On The Farm | World War II | Like Father Like (Grand) Son | Interview | Letters From Others | Helen Sigle Gossett | Sigle-Sperry Genealogy | Memories of Another War | Letter to Kansas Senators from Gene Koscinski | Lou Alexander, Navigator, Phone Call | Gene Koscinski Memoirs | VMail | Video of Richard Sigle | Our Guest Book

World War II

Learning To Fly

In the fall of 1941, I wanted to take Civil Aeronautics and learn to fly, but since I was not 21 years old, I had to have my parents sign the papers allowing me to take the course. They would not sign them. In the spring semester of '42 I was old enough, so I took the course on my own. I really loved to fly. Of course, all we had, in those days, to fly were Piper Cubs or Aeroncas. We flew Aeroncas. They were just a kite with a Maytag engine.

I finally got to take my cross-country solo flight. I flew from Hays to Russell to Alton and back to Hays. I flew a little out of the way between Russell and Alton so I could fly over home and deliver an "air mail " letter to my folks.

One day while I was planning a cross-country solo, I prepared a message for my mother and dad. I fastened the letter, with a weight on it, to a handkerchief which I made into a little parachute. I called my folks to tell them to watch for me. When I neared our farm, I flew low over the pasture near the house, and dropped the "air mail" letter. My folks saw it drop and were able to find it. My mother kept it and, years later, after her death, we found it in a box with other letters and souvenirs which I had sent home to them. I still have it!

After about 30 hours of flying, passing a Civil Aeronautics ground school test, and a flying test, I received my private license. It wasn't the first license issued, but compared to the number that have been issued today, it was a pretty early one at that.

To pass the flying test, I had to take a Civil Aeronautics inspector up and show him that I could fly. I had to be able to do stalls, Immelmann turns, Chaundells, climbing turns, emergency landings, and regular landings, along with spins. A spin consisted of two turns. I had to be able to recover it, or stop the turn right on two turns--no more, no less.

When I signed up to take flying lessons, World War II was on, and I had had to sign up for one of the Air Forces in order to get my flying lessons paid for by the government. I never did tell my folks that I'd had to do that!

Meeting The Weight Requirements

That spring, I went down to Fort Riley to enlist in the Air Force. I failed to pass the physical because I was overweight 11 pounds. I asked them to give me two weeks to take it off--and they agreed. I did everything I could think of to take off weight. I worked hard, ran night and morning after the cows, but I never lost a pound. I even took Epsom salts! Finally, five days before I was to go back, I quit eating and drinking water. In five days, I just took a sip or two of water a day. I lost 14 pounds, but I had just dehydrated. When I got down there, they had raised the weight requirement 15 pounds, so I wouldn't have needed to lose any at all!

Off To War

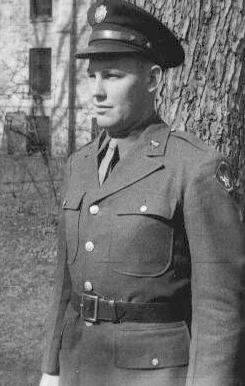

Pvt Richard B. Sigle

AAF 76th

Carroll College, Waukasha, Wisconsin

|

In February of 1943 I got my notice to report to Fort Leonardwood, Missouri, just outside of St. Louis. We were there for about a month learning to march and were issued our GI uniforms. We were then put on a troop train, and sent to college at Carroll College, Waukesha, Wisconsin. We were there for about three months--taking college courses that I already had taken at Fort Hays College. We did take about ten hours training in a Piper Cub. I tried to fool the instructor by pretending I had never had any flying instruction, but he caught on, and got mad because I hadn't told him.

On the train ride to Wisconsin, we had to sleep in a coach car right in the seats. We were covered, and I do mean covered, with coal dust and soot. It was the oldest train I ever rode, and certainly the dirtiest.

|

Approximately three months later we were shipped to SAAC at San Antonio, Texas--the hell hole of the Air Force. We were there for three months doing nothing in particular but going to ground school which everyone hated, and it was hotter than Hades.

Texas Hospitality

On the way down there, we were sidetracked and left on a siding out in the boon docks of Texas. There was a little old store in this place, not over a half dozen houses, and a garage or filling station. Some nice lady invited four or five of us to come to her house and take baths. Then we went to the store to buy some snacks. There, a couple of civilian drunks pulled a knife on one of our troops. It didn't take long for about a dozen soldiers to have him by the neck, arms, and legs, and throw him out. As we threw him off the porch, which was about three feet high, one of the soldiers kicked him in the rear, and I mean hard! Anyway our C.O. got us back on the railroad cars pronto! No more trouble there.

Acrobatics At Hicks Field. Texas

Next, I was sent to Fort Worth, Texas, Hicks Field, which was about 15 miles or so north of Fort Worth, for Primary Flying. There we flew a PT 19. It was a two-place, open cockpit plane. (In my military photo album are many pictures. Also, I have a Hicks Field year book.) There, we really learned to fly--doing everything including all acrobatics. (In my books, any pilot that doesn't know how to do acrobatics is not a pilot!) I had plenty of trouble learning to fly upside down, and also slow rolls. I'd always fall out of them by not holding the nose up. Finally my instructor got mad, and said, "If you do that again, I'll give you something to think about!" Well, it happened again, and he put me in an outside loop. I never want to do another one of those. I passed out like a light. We did loops, slow rolls, snap rolls, spins, and anything else we could think of to do, including rolling our wheels on top of a freight train that went through our area every afternoon.

Richard B. Sigle is in front

Basic Training at Coffeyville, Kansas

After leaving Hicks Field, we were moved up to Coffeyville, Ks., to Basic training. During the three months we were at Basic, we learned night flying, and flew the BT13 which was the most dangerous plane I ever flew. It would not spin very well.

It would go into a flat spin, and lots of times never come out. Our instructor told us that if we couldn't get it out after two times to leave it. I had altitude one time, and I rode one on a five-turn flat spin before I got it out, but I was ready to leave her!

My folks came after me for Christmas, and I took a kid from New York, Vincent Silvestor, home with me. We were gone from the base about three days, I believe.

Coffeyville was the only place in the Army that we never got enough food to eat. The mess officer was finally arrested for stealing money that was to be used for food for the soldiers.

War Bride

On February 2, 1944, I called Babe, who was teaching in a rural school near Fairport, and asked her to marry me. She agreed, and so I rode the train home, and arrived the morning of February 4. (Getting married was the only excuse one could use to get a three day pass!! Ha!) That afternoon, we went to Hays and were married by the Methodist minister that was there when we were in school--Rev. Joe Riley Burns. (It doesn't take an expensive, elaborate wedding to make for a beautiful, long marriage.)

Babe and I rode the train back to Kansas City on Sunday two days later. There I took another train to Coffeyville, and she went back home to teaching. Evea Jane marrying me was the best thing that ever happened to me.

|

Married February 4, 1944

|

Wash Out Fears In Pampa, Texas

At Pampa, Texas, we flew the AT17, a twin engine plane that was fairly nice. There we learned to handle the two engines and shoot landings, and do radio procedures with plenty of cross country flights. My partner and I were flying from an auxiliary field. There was a strong cross wind. The type of brake on that plane was an expander-type brake, and, if you used it too much, it would get hot and heat up the rim of the wheel. That would glow out the tube causing a flat. My partner had been flying, and that's what happened. Just as we took off, while I was starting to fly it, the tire went flat.

I went ahead, took it off, and called the home field. I was told to bring it on in there, and land it. I had no problem landing, and the tower told us to lock the controls, then they would send a truck out to get us.

After we got back to the hanger, we were discussing this with our instructor. The mechanics had fixed the tire, and started to tow it back to the hanger. In the meantime a strong wind came up, and, as they were taxiing it, it nosed over. Of course we were blamed for it, and they were going to "wash us out."

It went on for sometime, and still they had not held the wing board. Finally one Sunday, just before we were to graduate, they called us in to hold the hearing. We told our side of it, and when they called the officer in charge of the tower to give his side, he never showed. He had been shipped out to another field! That's the only thing that saved us--otherwise we would have been washed out, because an officer's word was supposed to be much better than a lowly cadet's.

Graduation

I graduated in the class of 44D in April of 1944 as 2nd Lieutenant, and got my wings as a pilot with a twin engine rating. After graduation, I took a train for home, and the route was via Denver. Helen, my sister. went on home with me. The train was so packed that we couldn't even get seats. Finally someone gave Helen a seat because she was holding a baby. I slept in the aisle sitting on my suitcase.

|

|

B-24 Training

After a two week furlough, Evea Jane and I were to report back to Liberal, Kansas, for training on a B-24, a four-engine heavy bomber. (More pictures in my album.) We were there about three months, and the only thing, as far as flying was concerned, that happened was on a practice mission. I flew the B-24 up home, and "buzzed" my home and Evea Jane's home, then flew it back to Liberal.

One time we took a cross country flight out west of the Grand Canyon and the Rockies. When we got over Pueblo, Colorado, we set our altimeter at their barometric, and flew at 50 feet above the ground there at Pueblo. We held 50 feet from there to Liberal. The instructor was showing me what difference in barometric pressure would do to your altimeter setting. When we got back to Liberal, we were around 3000 feet above the ground, yet the altimeter still said "50 feet". By calling the tower and getting a new barometer setting, it put the altimeter at the correct altitude reading for Liberal, and we landed it right on the correct elevation reading.

Maneuvering Orders

From Liberal I was transferred to a base near Fresno, California. There were four places a person could go for overseas training. Two were in California, one in Nevada, and one in Washington state. I was slated to go to Tonopau, Nevada. I did not want to go there because I couldn't take my wife, so I entered the hospital for a hemorrhoid operation, and stayed in the hospital (by collaborating with the doctor) until I could get on a shipment to Walla Walla, Washington. Evea Jane came up there to live with me for the three months I was there. I was getting a crew together, and getting overseas training. (Note from Donna: The story I always heard about collaborating with the doctor was this. My dad needed to stay in the hospital until an opening came for Walla Walla so my mom could go with him. He was ready to be released, so he took the thermometer and rubbed it on his sheets to heat it up to show he had a temperature. The doctor figured out he was doing this one day because he overheated the thermometer to the point that if it had been his real temperature he would have been dead. When the doctor found out why he was wanting to stay in the hospital, he worked with him.)

Training Missions

One night we were on a training mission, and were coming in for a landing, but, at that field, we had to make a pass over the field right down the runway we were going to land on. My copilot was standing up behind the instructor, and he saw another plane bearing down on us at a 90 degree angle!! He just reached over and pushed the control forward to keep us from colliding with the other plane.

Another time the instructor, a Major, that had been overseas two times, was showing us air to ground gunnery. He told me to fly the plane real low around the range so the gunners could practice shooting the ground targets as we flew by. I thought I was putting it low enough to suit him, but he said, "Let me show you." We had to RAISE for every little knoll on that course. The gunners said, "That was the first time they ever had to shoot UP at ground targets while flying!"

My Crew

I will tell you about the crew:

Baker was called home for two or three weeks because of the sickness and death of his father. We lost him for a crew member. (I offered to fly extra missions to get him back on the crew, but to no avail.) He was riding as crew chief on another plane, and it crashed, killing all aboard. He was replaced by PFC Frank Letezia, Chicago, for our crew.

Then the radio operator kept feinting sickness (vomiting, etc.) every time we went up. He didn't want to go overseas, so he was replaced with a Sgt. Al Oftedahl, from North Dakota. He was a screw off and a lover of ratings.

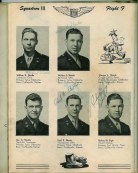

The Crew

|

Richard is top, right hand side

|

Click picture for larger view

|

We finally finished our training, and were shipped down to Hamilton Field, San Francisco, California, for the final staging. We were then put on an overseas troop train bound for the East Coast, and overseas.

We left Newport News, Virginia, around the first part of November in a convoy of approximately 15 ships. There was always the threat of enemy subs, and we had very little protection as far as fighting ships were concerned. We ate Thanksgiving dinner aboard ship in the Mediterranean Sea. We were about three weeks going over, and, at that time, President Roosevelt had decreed that Thanksgiving was the 3rd Thursday of the month, rather than the fourth Thursday. We landed at Naples, Italy. We were then put on a British ship and sailed around the boot of Italy, landing at Bari, Italy. It was about December 1, 1944. We were assigned to the 780th Bomb Squadron, 465th Bomb Group, of the 15th Air Force at Foggi, Italy, near Canosa.

Confrontation

I mentioned before that the radio operator was a screw off. For example, each of us on board ship had to go to classes. Even while at New Port News, we had to take training classes, such as going through the gas chamber to learn how to wear our gas masks in case of a gas attack. Sgt. Oftedahl was always looking for a way to get around doing everything. One day on board ship, he did not attend a class that I felt he should. I felt that if he didn't know what to do in an emergency, it might cause problems for everyone, so I turned him in to the C.O. (Commanding Officer, a Colonel.) I had previously confronted him time and time again, but to no avail.

Well, he had to report to the C.O., who chewed him out, but good. He also made him come to me and report that if I wanted to, I could "bust him"--take his Sergeant stripes away and make him a Corporal, PFC, or even a buck private. I told him I would not bust him this time, but one more such act, and that would happen. From then on I never had any more problems with him, although he would go the other way every time he saw me coming.

My First Missions

I was the first one of our crew to go on a mission. It was on December 13th, I believe, and then I went on another one the next day. I rode Copilot for a 1st. Lt. Dawson. I was so dumb that I didn't even know what flak looked like, but I do now. We had flown over the Alps and were starting down the bomb run, and I saw all that smoke ahead of us, right at our altitude, which was around 20,000 ft. I asked what that was, and was told it was flak. "You're not going to fly through that, are you?" I asked. Again, I was told that we were! Well, we got through O.K., and dropped our bombs, and headed back. It would take around 10 to 12 hours per mission when we flew the Alps. We didn't have any extra gas for joy riding. We were lucky to get home on what we had.

After we started flying our own missions with our own crew--which was after the first two when I rode Co-Pilot--I usually flew the number 4 position. That was a relatively easy position to fly.

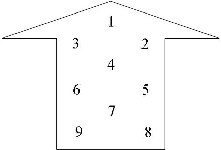

780th Squadron

No. 1 was lead plane, No. 2 & 3 were wing men. They flew just under and back of No. 1. No. 4 flew back of No. 1 and under it, and 5 & 6 were his wing men, etc. There would be four squadrons to the group, and the Lord only knows how many groups. I've seen over 2000 planes in the air at one time. They were going and coming. And that was just bombers. The fighters would be extra.

We hit many targets over the Alps in Austria, Germany, etc. I was one of eight planes that bombed Vienna, Austria--the most heavily fortified city in Europe. Our Squadron got lost from the group and wing, and our brave leader in No. l took us over the target. All eight of us limped back home. We had over 100 holes in our ship--two engines shot out, radios out, and left main tire shot out. We made a perfect landing on runway No 1, but because of the flat tire, and two engines out, our left side was pulled over into the mud between the runways. When we stopped, we were belly-deep in the mud. It took the ground crew three days to get it out, but at least all the crew were safe.

I was on the raid that bombed Regensdorf, Germany--the jet plane base of the Germans. They had 32 planes on the field. We got all but one, and we couldn't catch it. It took off down the runway ahead of us. The bombs were dropping right behind it, but it out ran them.

P-38's To The Rescue

One day we were limping back from a mission with our plane shot up pretty bad. We could not keep up with the formation. That was the kind of situation the Germans liked. They could then come in and pick off a lone plane. We called and called, and finally got a squadron of P-38s to fly cover for us until they had to return home ahead of us because of fuel. That was the prettiest sight I believe I ever saw. They were flown by black men, and they sure were good looking! By the time they left us, we were over some clouds, so we flew just on top of them so that if some German fighters showed up, we could duck into the clouds.

God Rode With Us

Another time, we were going on a raid, and our squadron started climbing and circling, trying to get in a group and wing formation. About the time we got to 10,000 ft, we hit a cloud bank, so they turned back and started letting down. Then all of a sudden, after letting down about 5,000 feet, they started climbing again and headed into the front. At about 10,000 feet, we hit the clouds, and in place of circling again, and getting on top of it, they headed right into it, and started climbing up through it. I told John (my Copilot) to put the plane in close, and stay right with him. I was watching, but a few moments later, I noticed our artificial horizon showed us in a steep turn. I glanced out and could not see any planes. I knew we had to climb out fast to keep from colliding with some of the other planes. I yanked the plane away from John, and pulled up in a steep climb with all power on. When we broke out, and got up a little higher, planes started popping up out of the clouds all around us. We were not touched. God rode with us again.

The Isle of Vis

In February, 1944, we were on a bombing mission of the marshaling yards of Vienna. We were gaining altitude when, all of a sudden, our plane tried to turn upside down. We could not imagine what had gone wrong. Just now and then it would act up and try to turn over. We were also having trouble holding the nose of the plane up, and keeping up with the formation. Because we were flying the slot position (#4), we had to move out of formation and ask for an early return.

We were over Yugoslavia at the time. Since we had to fly back over the Adriatic Sea, we decided to jettison our bombs in the Adriatic. It was an hour's flying time crossing the Adriatic, and flying over water with a plane that was not flying right was not a thing I longed to do. I had a crew of 10 men and much secret equipment on board. I decided, rather than risk crossing the Sea and maybe having to ditch the plane in the water, I would fly in to an emergency base on the Isle of Vis. That small island was off the coast of Yugoslavia.

I flew over the base and gave my crew the option of baling out or of riding it down with me. They all rode it down.

The field was only 1800 feet long, with a high cliff at one end and a saddle back on the other end. The saddle back had about a 30 degree slope on which the people farmed grapes. We had to drop down low over vineyards to land. There was no going around for another try because of the cliff at the other end.

I never got the plane on the ground until we were halfway down the runway. Even though I applied all the brakes that the plane had, trying to get it stopped, I still went off the runway slightly. We were safely on the ground, but I had burned the tires off in stopping.

All that was wrong was an elevator trim tab that had broken loose. Each time that it would flip one way or the other, it would try to turn the plane upside down. We got the trim tab fixed, and put new tires on, and by evening the plane was ready to fly again.

During the day, while the plane was being fixed, the CO took us on a tour of the island. He showed us the city in which the women swept the streets by hand. It was a very clean city.

That evening we unloaded all but enough fuel to get us home, as well as all ammunition, and any unnecessary items. We had to rev up the engines at the end of the runway with brakes on, and full power, in order to be able to clear the saddle back. We were so close to the vineyard that the people working there got down on the ground. They thought we might hit them. But we cleared the saddle back and were on our way back to home base!

Flying Wing

Near the end of our mission, and near the end of the war, everyone was trying to get as many missions in as possible to keep from having to go to the CBI Theater (China, Burma, India), rather than going home. I challenged our new operation officer for not putting us on the raids. Finally he said, "O.K., you'll be on tomorrow."

Well, he was going to fly position #2, and the General was going to lead us in #1. He put me on in #3 position, which is probably the hardest position to fly because of having to fly cross cockpit--and we were not even used to flying a wing position.

I told John that we'd fly her, and show them we could do a good job--which we did. The weather was very rough, and kept getting rougher all day long. Captain Dawson was going to show the General just how good he was, but he tried too hard because he was out and in all day. In fact, a lot of the time he would have his wing over the General's. On the way home from the target, and about an hour out from home base, I told John that the General had seen that we could fly, and it was getting so rough that, for safety's sake, we would move out. About that time Capt. Dawson thought, I'm sure, that, "Oh boy, I've got them now. We'll show the General just how good we are. He put his plane in really close to #1, and the General got scared he was going to hit his wing. He came on the radio and cussed--and I do mean cussed--Capt. Dawson out!!

Flying Home

That was the last mission we got to fly. It was only #16 for me, but they sent us back home to the States anyway. A few days later the war was over, and, after parades on our base, we were assigned a plane, and two extra men, and told to fly back home.

We were assigned the plane that always had an "early return." Something always was going wrong with it. Well, my engineer, Frank Letezia, and I went over that plane with a fine-toothed comb. Finally, we got down to cleaning the oil screens on the oil sumps. It was the night before we were to leave, but we stayed with it until we finished , which was in the wee hours of the morning. We rigged up lights, and had cleaned three screens, and each one had been all right. Frank said, "Shall we take this one out?" I replied, "Take it out." That last screen was completely clogged! We finished cleaning that up, and got a couple hours sleep before we took off for French Morocco in Africa.

When we were coming in for a landing, I opened a window because it was so hot. The wind coming in the window felt like a blast furnace. They told me after we landed that it was 127 degrees F. The next morning, the three planes (Weir's, Theena's, and mine) headed for the Azores in the Atlantic--a bunch of tiny islands that, on a map, are hardly more than dots. I doubt if any one of the islands are 10 miles across. Anyway, it was nice flying until we got close to the Azores and ran into rain with poor visibility. I asked Lou Alexander, the navigator, for anything that might be in our way--such as high hills or mountains. He said there was nothing above our altitude, which was about 100 feet.

We were flying instruments at the time, and we couldn't see very far at all. About that time, I glanced out and saw a mountain to our right. (I never did find out how high that was, but it was above our altitude.) We climbed to 500 feet, and called on the radio to get bearings, and to get clearance to land. We found the runway, which was four miles long and six feet above sea level, without too much trouble. We were glad to set down on it. We had to have a jeep lead us to parking as it was so foggy we could not see any parking or any buildings.

After eating and finding quarters to sleep (some of our men had gone to a show), I was too pooped to do anything. About 10 p.m., while I was getting ready to go to bed, an orderly came in looking for me. He said we were to be at the line (flight line) at 12 midnight for briefing--that we were going to leave here at 2 a.m. to fly into the States. He said the weather was getting worse, and they wanted to get us out of there before it got too bad.

Well, I got Wier and Theena to back me up, and when we were at briefing, and had listened for one and one-half hours on how bad the weather was, I made up my mind there was no way they were going to get me to fly that night. There were about a dozen or so crews that were to leave that night, but all the rest had been there for a few days. At the end of the briefing, I addressed the Colonel, and told him we had just landed that evening, had had no sleep, and we three crews were not going to take off. By morning the weather would be better or worse, and if it was better we'd go. If it was worse, I didn't want to be up in it, and it would be better flying in daylight anyway.

Ordinarily one doesn't tell a Colonel what you're going to do--you do what he says. But I had good luck and didn't get court martialed for disobeying his orders. He let us sleep from 2 a.m. until 4 a.m., have breakfast, and be on the line by 5 a.m. for briefing and take off. We did, we were, and we took off at 7 a.m. The weather was no worse, but it was no better. (I learned later that three of the planes that took off at 2 a.m. never made it to Newfoundland.)

When we arrived over Newfoundland, St. John's Airport was socked in, so we had to fly on to Stephenville, which was an hour more flying time. We were very, very low on fuel by then. It was overcast at Stephenville, but they told us, if we hurried, we might be able to make it. When we arrived, there was just one opening to let down through the clouds, and I dived her down through the hole and landed. Within 10 minutes of landing, it started snowing, and by morning there was a foot of snow on the ground.

After they plowed the snow off the runway, we took off for the good old USA. We flew down the St. Lawrence River. We could not tell when we flew over the mainland as it was islands and water for miles. Finally it got to be more land, and less water, and then all land. All of the land was covered with trees. We could see nothing else.

We landed in Connecticut. I can't remember the base. That's the last time I ever flew a B-24, and also the last time I saw all of my crew members. We were sent our separate ways by train for home for a furlough. After 30 days at home, I returned to Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas, where I was reassigned to a B-29 base in South Dakota. Before shipping out, we were told, if we had enough points, (it seems we needed 30), they would let us out or discharge us if we had certain orders. I knew I had the orders, but I was so excited that I could not find them. I also knew that I had a lot more points built up than I would need. Finally, after looking through my papers many times (and not being able to find the orders), I borrowed a set from a friend that were identical to mine, and that let me out. After I got out, I found mine! They were the 1st ones in the pile, but were upside down and backwards. Oh, hum! I sure was slipping, and I've been on the banana peel ever since!

I still had some leave time coming, so after I was discharged, I was sent home. I was not actually out of the service until all leave time was up. That was the day Japan surrendered. I am now sorry that I did not stay in the service. I could have retired with 20 years service in 1962, and had a good retirement income for life. Instead I was Honorably Discharged July 17, 1945, as a First Lieutenant in the Army of the United States (No. 0721014).

A Tribute

The following tribute is from a letter Evea Jane Sigle received from Richard's tail gunner, Frank Yanuzzi. It was written January 17, 1992: Lieutenant Sigle's professionalism brought us through the combat scene, and back to the States. I looked at Lt. Sigle as the same as my father. Lt. Sigle had the leadership ability to complete any job at hand. As you know, we flew a B24 back to the States from Italy, and landed at Bradley Field, Connecticut. Very quickly, in a matter of a few days, I was placed on a train for Ft. Sam Houston, Texas. The train was right there at the field. Lt. Sigle came to the train and said goodbye to me and to the others. That was the last time I saw him. Had he stayed with the military, he could have risen in Rank, up to a Colonel or General because he had all the ingredients and make up to keep a military Air Force active. He maintained himself as one in a million. He was a Pilot's Pilot.

An Interview

One of Richard's Great Nephews, Tim Keeler, asked to interview him for a school project on World War II. Click here to read the interview transcript.

Lou Alexander, The Navigator's

Lou Alexander was one of the officer's on my dad's crew. Through the power of Google, his son found my brother Arris and me, and I was able to record the phone call with my dad's Navigator. His story added and filled in a lot of blanks to this story.

Letter to Kansas Senators from Gene Koscinski

Gene Koscinski was another officer on the crew, the Bombadier. Click here for his letter to Kansas Senators.

The Family | Growing Up | Life On The Farm | World War II | Like Father Like (Grand) Son | Interview | Letters From Others | Helen Sigle Gossett | Sigle-Sperry Genealogy | Memories of Another War | Letter to Kansas Senators from Gene Koscinski | Lou Alexander, Navigator, Phone Call | Gene Koscinski Memoirs | VMail | Video of Richard Sigle | Back home