|

From the Prairies to the Skies | home

The Family | Growing Up | Life On The Farm | World War II | Like Father Like (Grand) Son | Interview | Letters From Others | Helen Sigle Gossett | Sigle-Sperry Genealogy | Memories of Another War | Letter to Kansas Senators from Gene Koscinski | Lou Alexander, Navigator, Phone Call | Gene Koscinski Memoirs | VMail | Video of Richard Sigle | Our Guest Book

Life On The Farm

Grinding Grain

Whenever we needed ground grain at the barn for the cows and horses, it was usually us kids' job to hitch up the horses to the grinder and grind the grain. The grinder was an old burr mill. It was staked down so that it would not turn or move when the horses pulled it. The horses were hitched to a long sweep arm about 15 feet long, and there was a guide pole to snap the inside horse to. The other horse was also tied to it. We usually used Old Jim and Bell to pull the grinder.

The grinder was bolted to a wood box made from bridge plank material about two feet wide, three and one-half feet long, and about 12 inches high. The grain, after being ground, dropped into this box. The grinder had a large bull gear that the sweep was fastened to, and it, through smaller gears, turned the bottom burr under the hopper. The hopper would hold probably 1 1\2 to 2 bushels of grain at one time. It had a large bolt that stuck up in the middle of the hopper which you could tighten down to grind the grain finer, if so desired. By taking the nut and other washers and spacers off, you could get to the burrs to change them from a fine burr to a coarser burr, also. All the grain went between the two burrs and was ground. It dropped into a small pan which had a paddle that turned. It pushed the ground grain out a chute into the wooden box.

It was our job to the keep the hopper full by carrying the grain in buckets from the barn (later a granary) and dumping it into the hopper while the horses were on the other side of the circle. We then scooped the ground grain from the box, carried it into the barn with buckets, and dumped it into two 55 gallon barrels. We also had to keep the horses going. Sometimes, once we got a little wagon, we would hitch it on behind the horses and get a free ride. This grinding job would take about 2 hours to grind 2 barrels of grain.

Richard and his older brother Harvey grinding grain and hitching a free ride.

Shocking Wheat With the Grasshoppers

During the dry years of the 1930's, and even up to '36, after the drought was broken, there weren't too many of the small farmers who didn't cut their wheat with either a binder or a header. It was in 1937, I think, that my dad had used a binder to bind his wheat, and he and Cleo did the binding. I was the lone person doing the shocking. Shocking was standing the bundles of grain with the butts on the ground and the head of wheat leaning against each other. Probably 20 or 25 bundles were put in each shock.

|

It was so hot and dry that year, and the grasshoppers were really bad. It was a problem to keep the water jug from being "decorked!" I used an old crock jug wrapped in gunny sack, and wired it in place. Usually, I had a gallon, or a two-gallon, jug with a cork for a stopper.

It was so dry that year, and the hoppers were so bad that I had to cover, completely, the jug in a shock of wheat. Otherwise the grasshoppers would eat all or part of the cork out of the jug to get to the moisture. Sometimes I would hide my jug in a shock, then I couldn't find the right shock when I wanted a drink. I used to take a lemon to the field, also, and many times the grasshoppers would eat the peeling off the lemon.

After I finished shocking Dad's fields, I got a job at Lyle Mitchell's helping shock their wheat. The grasshoppers would cover all the fence posts and the trees on the sides where the shade was. They ate all the leaves from the trees.

We would poison them with bait by mixing poison with sacks of bran, orange and lemon peelings, potato peelings, and any other peelings or garbage one might have to mix in the batch. We killed hoppers by the millions.

I worked for $3 a day for the Mitchells. Two others were helping, Rubin Oslin and Francis Roe. Both told dirty stories from morning till night. After so many of them, I'd get disgusted and go off by myself to shock alone.

|

A Close Call With The Disc

It was a warm, beautiful day in early spring. I was about 12 years old and like most kids, wanting to do things that should have been done by someone older. However, I had talked my dad into letting me disc a few rounds with four head of horses hooked onto a nearly-new disc. Dad went about one-fourth mile away in the same field to help my brother, Harvey, get started planting. As I was nearing the end of the field where they were, I saw Dad start walking toward me. I knew he was ready to take over my job. I had on the new pair of gloves my folks had bought me, so I really wanted to prove how they helped me drive those horses! Another round would surely prove my point!

One of the horses, old Jim, was noted for being slow. I didn't have a whip to spat him with, but I had a short stick that I used to poke him in the behind. It was too short to reach him, so I stepped up on a diagonal brace that came from the hitch on the disc to the middle of the frame. I was going to poke old Jim up a little bit, so I could go another round. Well, anyway that was my intentions--but the best laid plans sometimes go astray. As I stepped up onto the brace, I missed my step and fell under the new disc. It went over all of me from ears on down, with my face buried in the dirt.

When I came out from under the disc, I got up and said, "Whoa!" The horses stopped, and I dusted myself off. My dad had seen the whole affair, and came on the run. He made me strip right there beside the disc to see if I were hurt. He found only one cut on the back of my neck about 1 l\2 inches long. That was the first time I'd ever seen my father cry.

Hiring Out

When one could get a job in those days doing anything that would earn a coin, he did it. Many times I helped fix our neighbor's water supply tank. I would get inside in rubber boots when it had leaked until it was down to below boot top level, and apply tar, a rubber washer made from an old car tire tube, and a bolt with a big metal washer on it. I would hold all that while someone--usually Mr. Winder--would apply tar, a rubber washer, a metal washer and a nut to the outside. I would usually earn a dime--sometimes only a nickel, and, once in a great while, a quarter.

After one of those big jobs, Mr. Winder asked if I'd want a job helping list (plant) corn. Man, was I excited. He offered me 50 cents a day, plus dinner and supper. Of course, I would have to drive four head of horses on a planter. My folks agreed, and I worked for about two weeks. The only way I was man enough to get it out of the ground, though, was to hook my feet under the pedals (where my feet rested), and unlatch the lever. By using both hands, I could raise it out as long as the horses were still going. Sometimes I would start too quick, and I would get it out before I'd get to the end. It went into the ground easy as long as the horses were moving, so I'd put it in a little ways, and then gradually let it go in to the right notch just a notch at a time. That made for poor driving--so my rows weren't as straight as a snake crawls, but you get more seed planted in a crooked row than you do in a straight one!

Topping Feed

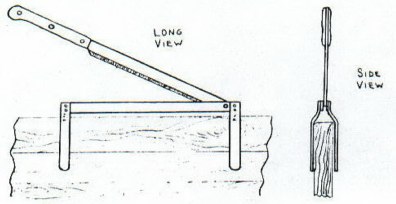

Topping feed, when I was a kid, was done with a knife approximately two feet long, with a handle on the knife about two feet. This bolted between two pieces of straight flat iron approximately 3\8 x 3 x 26 inches. It had two legs on each end to fit over the side board on the rack, such as this:

The feed bundles were held up across the irons, and someone in the rack would bring the knife down and cut the heads off the bundle. The heads would fall into the wagon or hay rack. The person on the ground would lay the topped bundle down, then get another, and the person in the wagon would bring the knife down on the next bundle. This went on until that shock was completed, and then we'd move to another shock.

When the rack was full of topped heads, they would be stacked. When the farmer had all the heads stacked, he would hire a threshing machine to come in, and the heads would be pitched into the thrashing machine to thrash the grain--a very slow, hard process to get grain.

In those days there was no such thing as milo. It was brought in and developed after WWII. Later people rigged up a cutter bar on combines to cut heads off and thrash them. The sickle bar was turned up so the guards pointed up. Then the combine would be pulled up to a shock. The heads of the bundle were held toward the auger or canvas (depending on the type of machine), and the vertical sickle would cut them off. This was much easier and faster, but it was a great boon to the farmer

when the short milo was introduced. It could be cut while standing in the field, and thrashed all at the same time. This eliminated having to bind, shock, top, and thrash it.

The Family · Growing Up · Life On The Farm · World War II · Like Father Like (Grand) Son · Interview · Letters From Others · Helen Sigle Gossett · Sigle-Sperry Genealogy · Memories of Another War · Letter to Kansas Senators from Gene Koscinski · Lou Alexander, Navigator, Phone Call · Gene Koscinski Memoirs · VMail · Video of Richard Sigle